When I was a child, we lived in a flat with no garden. All the flowers I knew were on stamps I collected, or cards in packets of Brooke Bond tea I pasted into stiff little albums that had to be sent away for. From the bright flat images next to the old songs of their names – cowslip, butterbur, meadowsweet, forget-me-not – I sensed that plants were powerful, even though they were small, soft and, as far as I knew, silent. So I learnt young that there was such a thing as paradox, that life could contradict itself and things weren’t always what they seemed.

The flowers whose names chimed in my head, like portable poems, wild and cultivated, seemed to grow in an imaginary realm, a world I read about in books where people lived in houses with gardens and gardeners, exotic apparatus like wheelbarrows and spades. They belonged to people who weren’t us, with different names and different lives – Alice Through the Looking Glass and Mary in The Secret Garden, across the ocean Anne of Green Gables. My mother’s name was Lily and, in the absence of a garden, she filled our flat with houseplants she’d water every Saturday morning and feed a magic potion from a fat brown bottle.

I was twenty-four before I saw a snowdrop and knew that was what I was looking at, consciously paired the word with the three-dimensional flower growing out of hard winter earth. By then living in rural Northumberland, as the seasons changed and flowers appeared in garden, woodland and hedgerow, I remembered all the names I’d forgotten I ever knew. It was a revelation that echoed Adrienne Rich’s reflection on poems – that they ‘are like dreams: in them you put what you don’t know you know.’[1] Flower and word spoke to each other – in the botanical texts I read as well as the poems I wrote. I got my hands dirty in the soil, watching and learning how different plants grew, looking up where they came from and how they were named. Moving between inside and outside, self and other, I experienced a kinship and intimacy I found nowhere else.

When Georgia O’Keeffe took the flower as muse, she felt her portrayals were misinterpreted. How she explained it is a touchstone for me:

A flower is relatively small.

Everyone has many associations with a flower – the idea of flowers. You put out your hand to touch the flower – lean forward to smell it – maybe touch it with your lips almost without thinking – or give it to someone to please them. Still – in a way – nobody sees a flower – really – it is so small – we haven’t time – and to see takes time like to have a friend takes time. If I could paint a flower exactly as I see it no-one would see what I see because I would paint it small like the flower is small.

So I said to myself – I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me, but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it – I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers… Well – I made you take time to look … and when you took time … you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower – and I don’t.[2]

Like a friend, a flower is never just one thing: both subject and object, it is a composite form, a layered text. In the field, however long you look at a flower, however closely you observe it, the flower shifts shape at different times of day in different kinds of weather. You have to get on your knees, down at the flower’s level, to inspect it properly. I need to put my glasses on and lean in very close. If you use a botanical hand lens, the scale changes even more: stigma and stamen, pollen grain or droplet of nectar are magnified, so you can imagine how it might look to a foraging bee. This is ‘reading the flowers’, via our word ‘anthology’ from the Greek, which also means ‘gathering the poems’ – just one seed of a long association of plant and book, word and root, folio and leaf.[3]

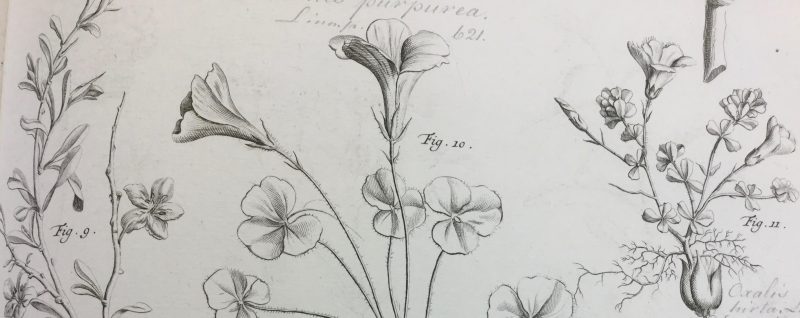

Images from the Margaret Rebecca Dickinson Archive in the Natural History Society of Northumbria’s Library at the Great North Museum: Hancock, Newcastle upon Tyne.

[1]Adrienne Rich, When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision (College English, Vol. 34, No. 1, ‘Women, Writing and Teaching’ (Oct., 1972), pp. 18-30.

[2]Georgia O’Keeffe,‘About Myself’, in Georgia O’Keeffe: Exhibition of Oils and Pastels, exhibition brochure (New York: An American Place, 1939).

[3]Linda France, Reading the Flowers (Todmorden: Arc Publications, 2016).

A lovely post, thank you. I too collected those Brooke Bond cards! Amazingly I still have five albums, including Wild Flowers series 2 and 3. Snowdrop is the first flower in series 3.

Thanks. Yes, I still have a couple too – a strong sentimental attachment. Ditto my stamp albums. Have loved paper ephemera ever since my childhood – connected somehow with my love of flowers – haunted by impermanence. Lx